Selected Stories from

The Grannie Annie Family Story Celebration 2013/2014

— Stories dated 1600–1945 —

1.

The Story of Chief Biauswah

northern Wisconsin, USA; late 1600s

One day Chief Biauswah,* who was one of my great- . . . great-grandfathers from the Ojibwa tribe, was out hunting. When he got home, his village had been burned and destroyed. There were only a few survivors. He found a trail made by the villagers that had attacked his village, and followed it. When he got to their village, he realized it was the Fox tribe.

The Fox tribe had captured a young boy and an old man, whom they were going to torture then kill. First they wrapped the old man with birch bark, lit him on fire, and made him run between two lines of people, who would beat him as he ran.

Chief Biauswah looked at the boy, and it became clear to him that the boy was his son, whose name was Biauswah II. The Fox were hanging the boy up on a post, getting ready to burn him at the stake.

Thinking only of his son and not of himself, Chief Biauswah jumped out of a hiding spot. He said he was the chief and that the boy was his son. He tried to get them to stop. He cried out, "My little son, whom you are about to burn with fire, has seen but few winters. His feet have never trodden the war path. He has never injured you. The hairs on my head are white with many winters, and over the graves of my relatives I have hung up many scalps, which I have taken from the heads of your people. My death is worth something to you. Let me take the place of my son so he may return to his people."*

The Fox people were astonished but agreed to this, for they had long desired to kill the chief.

They released the boy and tied the chief to the stake. They scorched him to death. Biauswah II became the new chief.

* Pronounced bee-ah-swah.

** These are the chief’s words much as they have been passed down for centuries.

Elon Johnson; Minnesota, USA

2.

The Nine-Year-Old Goose Killer

St. Louis, Missouri, USA; 1911

It was the winter of 1911 in St. Louis. My great- great-grandma, Helen Benner, was forced to raise the family by herself, because her mom had died and her dad had to work all of the time. Helen had three younger brothers — Eddie, Harry, and George — and two younger sisters, named Dorothy and Gladys. George was nine at the time, and no matter where George went, he always seemed to find trouble.

One day, close to Christmas, Helen’s dad’s boss gave the family a goose for Christmas dinner. There were two problems: one, the goose was alive, and two, the family had to walk three miles downtown to pick the goose up. Helen had to babysit Dorothy and Gladys. Her dad, Eddie, and Harry were off working, so that left only George to pick up the goose and take it home.

When he arrived downtown, George realized that he didn’t have anything to take the goose home in, so he decided that he was going to carry the goose home in his arms. However, the goose did not like this, and it started to peck and flap its wings at George. He then realized that carrying the goose was not an option. So he devised the best plan he could think of. First, George got a rope. Second, he tied the rope around the goose’s neck, and third, he began to walk the goose home like a dog on a leash.

Soon after George began his trip back, he realized it was taking too long to walk home, so he decided to run. However, the goose could not keep up, and it was soon strangled. The goose continued to become heavier, but George assumed it was just struggling with the rope, so he didn’t look back.

When George arrived home, he found out that the goose hadn’t been pulling on the rope; it was dead! George had dragged it two of the three miles back. The dead goose was covered in dirt and rocks, and the skin had been scraped off. Naturally, the family couldn’t eat the goose, and everyone was furious with George for ruining their Christmas dinner.

A couple of days later, George had forgotten how mad he was about the goose and was throwing his sister Dorothy’s hat into the air. One time he looked away as he tossed it and was surprised when it didn’t come down. He looked up to find that it was resting on a kerosene lamp and it was on fire. It could have burned the house down.

On Christmas morning all of the excited kids looked in their stockings to find oranges — all of the kids except George. When he looked in his stocking, all he found was a big lump of coal. George’s antics that year led to him becoming known as “the nine-year-old goose killer.”

Jack Christian; Missouri, USA

3.

Arranged Marriage

Bangalore, Karnataka, India; 1921-1939

You may have parents or grandparents that are married. But at what age did they get married? Did they get married at 27, 30, or 35? Maybe even 23! But have you ever heard about arranged marriages in India? My great-grandmother had an arranged marriage and got married at just age 13! Can you believe that?

My great-grandmother Lakshmi was born in 1921. I call her “Muthajji.”* At age 3 she knew whom she was marrying! She met my great-grandfather (whom I never knew) at age 8. This was at the bride-viewing in 1929. The bride-viewing was where my great-grandfather, age 12, met Muthajji, age 8, for the first time. Muthajji and my great-grandfather then decided if they wanted to marry or not. As part of the deal, Muthajji’s family agreed to pay for my great-grandfather’s medical school. The wedding would be held on one condition — if Muthajji’s body was able to have babies. Then the couple would marry. Muthajji would not be able to live with her husband until he finished his medical school and his residency.

When Muthajji was 13, the wedding took place in Bangalore, India, under a mandap made of flowers. A mandap is a canopy usually made of flowers and silk. Muthajji was very nervous at first. She was also upset, because she thought that she should be able to pick her spouse. When she was 8, her parents had made the decision for her. She hadn’t had a choice. When she was 13, she wanted to have a choice. She knew she had to marry my great-grandfather, but she was upset. She secretly wanted to make her own choice, but she would never disappoint her parents. Hindus never disappoint their parents. To Hindu children, parents are the world. Their word is law.

In 1939 my great-grandfather completed his medical school and residency. At that time my great- grandmother was legally allowed to live with my great- grandfather. Love came eventually, but it was not there at first.

In the end Muthajji was married for fifty-five years. She made her parents happy. She had two children and ended up living a life of contentment. She eventually came to realize that, indeed, her parents knew best.

* Muthajji (MOOTH-uh-gee), meaning “great-grandmother,” combines muthu (pearl) and ajji (grandmother) in a name that is informal yet respectful.

Colin Kowalski; New Jersey, USA

4.

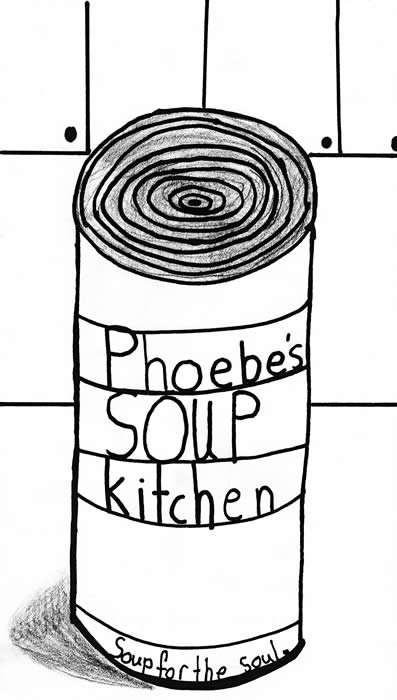

Saving Tampa

Ybor City, Tampa, Florida, USA; c. 1930s

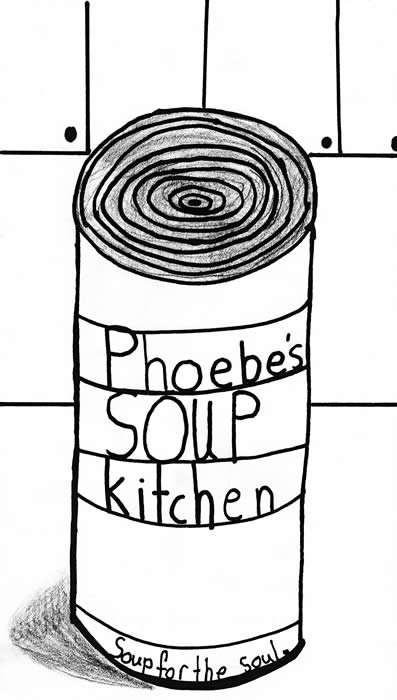

During the Great Depression my great-great- grandmother Antonia came home from the worst day of work. She owned a grocery store called “American Beauty” in Ybor* City, the Latin Quarter in Tampa, Florida. When she came home from her little grocery shop, she sadly complained to her mother, Phoebe, “All the vegetables are going mushy and brown, since nobody can afford them. So now the store is struggling to stay open.”

Phoebe thought for a little while, and then finally said, “I can make soup out of the bad vegetables for you to give out to all of the hungry people for free. Maybe when people can afford things again, they will remember that it was your store that made the soup, and they will shop there.”

They had money to spare, so they ordered more fresh vegetables and made free soup out of those after they used all of the old vegetables. People enjoyed the soup and realized how generous Phoebe and Antonia were.

Phoebe made the soup in huge pots that could make about seven batches at once. She had two extremely wonderful stoves, so the line went quickly — almost as fast as Phoebe could make the soup. She did not waste any time at all. The line for her vegetable soup was so long, it went all around the block. Phoebe was married to a gypsy’s son and had five children — Antonia and four others. The four other children came over to wash the dishes and serve the soup to the hungriest people they might ever have seen in their lives.

A few years after the Depression, when Phoebe died, all of the doctors and lawyers and more of the important people in Ybor City came to her funeral and said, “If it was not for her wonderful vegetable soup that she often made during the Great Depression, we would have died of hunger, and everyone else tragically would have died without our service.”

After Phoebe and Antonia started the very first soup kitchen in Tampa, more soup kitchens started around that area, so a few years later they were not doing all the work.

This is how my great-great-great-grandmother and her daughter saved all of the starving residents of Tampa.

* Pronounced EE-bor.

Clara Rominger; Alabama, USA

Illustrator: Madison Nowotny; Missouri, USA

5.

Times of the Holocaust

southern Poland; northern Austria; 1937–1948

When I was fifteen, I was taken from my home in Lublin, Poland. After being detained in different places in Poland for five years, I was sent to Austria and put to work in a factory. While I was there, one of my jobs was to make sights* for the guns on the Messerschmitt, the first German jet-propelled combat airplane. However, this was not my favorite work. I was used to working outside on my father’s farm, not inside a factory like this. But I had no choice about the work I was doing. I did have a choice about how to do it though. So instead of doing my job right, I moved the base of the sight too far one way or the other, making the gun miss its target when fired. I also put sugar in the engines to make them seize.

Why did I do this? I did this because I was forced by the Nazis to work in a labor camp because I refused to join the German Army when I was asked. I did anything I could to work against the Nazis. I even used shrapnel I found on the ground to cut communication lines. I worked against the Nazis because I was not on their side. I didn’t agree with what they were doing. I was determined not to fail. I was also determined to live.

I lived by doing what I was told, and that’s how I somehow lived through eight years of my life. Once one of the “icemen,” a soldier in a special unit of the Nazis, told me to clean his boots, so I did. Then later the same “iceman” came back and saved me from being killed. But unfortunately my friends were not so lucky.

Another time, a German guard sent a group of us to take showers. But then another guard, who was Austrian, sent me back to the barracks because he thought I was a good worker. I ran back with my clothes in my hands. No one came back from that shower. Gas was released in the showers, killing everyone. I had been saved again.

My real freedom came in 1945, when I was finally freed from the Nazis by American and Russian troops. I immediately wanted to join the United States Army so I could fight against the Nazis for real.

Three years later I immigrated to America, arriving at the navy depot in New York. Though I look as round as Santa now, I actually weighed only fifty pounds when I got here. I lived with my mother’s sister in North Thamesville, a part of Norwich, Connecticut.

Though life was different in America, I had the chance to live it. I was lucky I was alive. The lessons I learned in concentration and work camps, like following directions but also never giving up, helped me in America. I also never forgot that doing something little could make a big difference.

* A sight is a device on a gun that helps the shooter aim at a target.

Paxton Hilgendorff, great-great-nephew of narrator; New Jersey, USA

6.

Lali—The Legend

Uluberia, West Bengal, India; 1942–1948

The man-animal relationship can be an unbreakable one, and our family legend rightly proves it.

It was the year 1942. World War II would continue for two more years, but it had already had its effect on India. India had to send tons of food and thousands of soldiers to aid the Allies; after all, we were part of the British Empire. The taxes were already proving fatal for the farmers, but the war was something different. There was always a fear of Nazi and Soviet attacks, but there also was a sure possibility of famine and plunder.

My grandpa was then studying in a small school in a minute village. By that time, the famine had already started, and he was soon removed from school. After all, how will a child study while he is dying of hunger? Soon the schoolhouse was empty — not a single child came. Meanwhile, my grandpa had to work in fields with his mom, dad, and brothers so they could get one square meal a day. It was laborious, but at least they were not dying.

Then one day his dad brought home a small calf,

totally red in color. Grandpa described it as the cutest being he had ever seen, and affectionately called her “Lali.”* Soon all his time went into the care of the calf, and their bond started to flourish. In nights when the mosquitoes were scarce, Grandpa used to sleep near Lali,

trying to protect her from all harm. In the meantime my great-grandfather passed away due to malaria.

Soon the calf was a healthy cow and was able to produce milk, and milk meant that there was another source of income. For a time all went well. My grandpa’s mom was a tough lady, and she somehow managed to provide for the household by planting rice with her sons. Grandpa’s job was to milk Lali and sell half of her milk in the nearby market. “She gave enough milk that even after selling two gallons we still had lots of milk,” he boasted proudly. Due to the milk produced, Grandpa’s family was able to buy a large land expansion, and farming also started bringing money into the house.

After the war was over, India became independent. Grandpa’s cow was then in her golden years. Grandpa was again continuing high school and had shown an extreme interest in music. His elder brother had got a job, and the house was renovated.

One day Lali took everyone by surprise. Her calf was constantly ramming itself on Grandpa’s mom. And suddenly, out of nowhere, Lali came running like mad and gave a full-impact blow to the adolescent calf. That day my great-grandmother was injured gravely, but if it had not been for Lali, she would have died. The bond between Lali and our family was so strong that, ignoring her own maternal feelings, she saved her keeper from her own calf.

Even many years after her death, Lali still remains in our hearts.

* Lali (LAH-lee) is an affectionate form of the Hindi word laal, which means “red.”

Malab Sankar Barik; Uttar Pradesh, India

Illustrator: Regan Carpenter; Missouri, USA

7.

Oh, Say Can You See

Queens, New York, New York, USA; 1943

It was the year 1943. All over the world, the havoc of World War II was raging. Bombs shattered over London as German fighter planes released their explosives. Guns tormented the French as the Nazis infested their land. Troops invaded Italy as the Allies seized their target. All the while, the pencil of Lois Franks scratched the paper. Lois, my grandmother, was hard at work finishing her homework for Mrs. Fowler’s third grade class. She was also hard at work scheming some way she could hold the flag.

At PS 127 elementary school, if you had a family member fighting in the war, you could stand up and hold the flag while your class sang the national anthem. To Lois and the other children, this was a great privilege. So as Lois walked to school, she was confident that she would hold the flag. Her brother had not only fought for his country but had died for it. There was only one small obstacle: Lois had no brother. However, her desire outweighed this minor difficulty.

Lois arrived at East Elmhurst School in Queens, New York, with her twin sister, Ruth. She entered the classroom and went to her desk, where she immediately envisioned what it would be like to hold the flag that day. When Mrs. Fowler finally asked for a student to come hold the flag, Lois raised her hand sky-high.

“Lois, do you have a family member fighting in the war?” Mrs. Fowler asked politely.

“Not anymore, Miss. My brother Harry died in action.”

“Oh, how dreadful! Here, you can stand on the right of the flag, and Ruth can stand on the left.”

Ruth! In remembering her fictitious brother, Lois had forgotten her factual sister. Her heart raced — the lie had been in vain. If you had a sibling, you only stood on one side of the flag. However, this was not Lois’s only fear. The uncertainty as to Ruth’s action tormented Lois, who knew there was nothing left to do.

Ruth stood . . . and crossed to stand on the opposite side of the flag. Relieved, Lois felt convinced that she would not be punished for this lie. True, she didn’t get to hold the flag, but this way, unless some unforeseen crisis arose, she was safe. Ruth stood . . . and crossed to stand on the opposite side of the flag. Relieved, Lois felt convinced that she would not be punished for this lie. True, she didn’t get to hold the flag, but this way, unless some unforeseen crisis arose, she was safe.

Nothing did arise — at first. Then, one ill-fated day, Mrs. Franks and her daughters were at the grocery store. In the aisle next to her mother, Lois spied Mrs. Fowler heading straight for Mrs. Franks. As the women spoke,Lois helplessly watched the expressions change on the two ladies’ faces. She was caught.

After a good spanking, Lois reprimanded herself for her poor behavior. She reminded herself that standing next to the flag — even holding it — was by no means worth the pain of knowing she had done wrong. Nothing is worth the price of a guilty conscience.

Marissa Little; Pennsylvania, USA

Illustrator: Abigail Ruckman; Missouri, USA

8.

The School That Fell from the Sky

Ea Ea, New Britain, Papua New Guinea; 1943

Imagine waking up dangling from your parachute, stuck in a tree in the middle of a jungle in Papua New Guinea during World War II. Your plane was shot down. Well, that’s what happened to my great-uncle’s father, Fred Hargesheimer.

It was June 5, 1943. Fred was flying a P–38 Lightning fighter plane in the 8th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron. All of a sudden his plane was shot down by the Japanese. Fred leaped from his plane, which was on fire, with his parachute.

In time Fred fell from a tree in the middle of the jungle. He foraged for food for thirty-one days. He ate snails for food and drank polluted water. While he was eating one day, he heard music. He hoped that, if he went over by the melodic music, the people wouldn’t turn him in to the Japanese. He went over there, and it turned out they were native New Guineans collecting water. They did not turn Fred in, but took care of him and nursed him back to health. Surprisingly they even hid him when the Japanese came to the village looking for the American pilot.

While the villagers cared for Fred, he suffered from malaria. He had a terrible fever and was in a lot of pain. More days passed, and it was clear that songs and prayers were not enough. For ten days Fred could not eat. For the next ten days the only thing he could keep down was mother’s milk from his native friend Ida. He had survived yet another challenge!

When the villagers were able to, they got a message to a British Coast Watcher. Finally Fred was rescued by a submarine and returned to America.

In honor of this village, Fred sent money to build a school in the village. He visited several times. Fred later wrote an autobiography about his experiences and titled it with the name that the villagers use for their school. They call it “the school that fell from the sky.”

Peyton Kopel; Minnesota, USA

9.

The Silver Spoon

Ardennes Forest, Belgium; 1944

I was drafted into the U.S. Army in the spring of 1944 during World War II. By mid-December I found myself in a dense forest in Belgium under surprise attack by the German forces. This would eventually be known as the “Battle of the Bulge.”

The sharp winter air cut through my clothes as I loaded another round of bullets and shot them into the madness. Suddenly I flew through the air and felt a searing pain in my chest. I reached down into my front shirt pocket and yanked out the silver spoon I was carrying. The bullet that had knocked me over was fused to the spoon.

The spoon wasn’t just any old spoon. My roly-poly mother had given it to me. My mother had immigrated to the United States from Russia in the early 1900s and spoke mostly Yiddish. She was well known for being an amazing cook and for being incredibly stubborn.

On the day I shipped out, she gave me a firm hug, smelling of cinnamon, and a care package. The care package contained gray wool socks (which I am currently wearing), home-baked raisin challah, and a sterling silver spoon, which we used on Sabbath. She told me to wear the socks to stay warm, to eat the food to stave off hunger, and to carry the silver spoon in my front shirt pocket to remind me of home. I told her I didn’t need the spoon, but she shook her sterling-haired head sadly and placed it in my hands. I still refused.

My brother Jay, who has slick brown hair and our mother’s stubborn streak, pulled me aside and asked why I wouldn’t take the spoon. I didn’t really have a reason. Jay told me to carry the spoon so our mother would be happy. I heeded his advice and brought the Sabbath spoon with.

As I lay in the midst of the raging battle, I examined the spoon. It looked like a bent piece of junk, but I didn’t care. That spoon was my savior. That very same spoon, which had served me matzoh ball soup and helped me fling peas at Jay, had taken the brunt of the bullet and saved my life. My mother’s love and our religious faith were embodied in the spoon, and that is what truly saved me.

I will never polish the spoon. I will never remove the bullet from the spoon. I will carry the spoon with me forever. I’m Lenny, and my mother’s special sterling silver spoon saved my life. And if you ever see me, I will always have my silver spoon.

Amy Tishler, great-great-niece of Lenny; Missouri, USA

10.

Seagull, Sir

Little Creek, Virginia, USA; 1944

It was a warm day in Little Creek, Virginia, and the sun was shining on my grandpa’s face. Grandpa was at a military base, training to be in the U.S. Navy for World War II. It was the day that their uniforms were to be inspected. The inspector expected the troops to have spotless, pristine white uniforms when they arrived at the inspection line. In order to get to the clearing for inspection, they had to march about a mile through the wooded forest. The troops were not allowed to speak during the hike through the woods or during the inspection.

My grandpa advanced through the dense woodland, thinking to himself that nothing could go wrong. He had nearly reached the inspection line, feeling he would get a favorable report from the inspector, when a seagull flying overhead dropped its load on my grandpa’s right shoulder. My grandpa frantically tried to think of something he could use to wipe the bird poop off, but he didn’t find anything. He couldn’t even locate a handkerchief. The only thoughts going through my grandpa’s head were thoughts of wonder and worry — thoughts like What will they do to me? and They’ll lock me up for sure. Because the troops weren’t allowed to talk, my grandpa couldn’t ask if anyone had a piece of cloth to wipe the mess off. My grandpa advanced through the dense woodland, thinking to himself that nothing could go wrong. He had nearly reached the inspection line, feeling he would get a favorable report from the inspector, when a seagull flying overhead dropped its load on my grandpa’s right shoulder. My grandpa frantically tried to think of something he could use to wipe the bird poop off, but he didn’t find anything. He couldn’t even locate a handkerchief. The only thoughts going through my grandpa’s head were thoughts of wonder and worry — thoughts like What will they do to me? and They’ll lock me up for sure. Because the troops weren’t allowed to talk, my grandpa couldn’t ask if anyone had a piece of cloth to wipe the mess off.

As Grandpa stepped into line to be inspected, he knew he would be punished in some way. He prepared himself for the worst as the inspector slowly made his way down the long line of troops. There was not a sound. It was so quiet that my grandpa could hear his own heart pounding in his chest like a Chinese gong. When the inspector reached my grandpa and looked over his uniform, he paused to stare at the stain. Grandpa looked the inspector straight in the eye and said, “Seagull, sir.” The inspector smiled and moved on to the next in line, not saying a word to my grandpa.

Braden Luechtefeld; Missouri, USA

Illustrator: Alyssa Cannon; Missouri, USA

11.

Even Baseball Isn’t Safe

near Berlin, Germany; 1945

One day in Germany my grandfather Howard was playing baseball with his army buddies. Little did he know he was in for a surprise. He was relieved that World War II was over and that he could just have a little fun until he went home. It was a few days until his infantry unit would go back to America. So what better way to pass the time than America’s pastime: baseball. Baseball had always been Howard’s favorite sport. He was sick of all the fighting, all the terror. He didn’t want to worry about anything.

They were playing in a field, and the grass was tall, and fresh with morning dew — just grass as far as the eye could see. Howard loved places like this. They relaxed him.

“Howard, you’re up,” called one of his army buddies. Howard grabbed his bat and sauntered to home plate. But then something by home plate caught his eye. It looked shiny and was lying in the dirt.

It’s probably just scrap metal, Howard thought. He went over to get a closer look, then brushed his hand over the thing to remove the dirt covering it. Guess what he found. It was a mine!* Howard took it all in, thinking it was his last moment on earth. He waited a few seconds. Finally, when he realized he wasn’t dead, he called to his comrades, “Guys, we have a mine over here!” His friends sprinted over to see the mine.

“Holy cow,” said one of his buddies, “it must be left over from the war. I guess it was never activated.”

“Everyone back away,” warned another man. “It could still be active.”

None of them knew what to do. Then something clicked in Howard’s brain. They were holding Nazi soldiers prisoner in a camp nearby. He hoped one of the soldiers had deactivated mines for the Nazis. He ran so fast to the camp that even sound was begging for him to slow down. When he got there, he told the guard he needed one of the soldiers.

“But what if he escapes?” the guard asked.

“It’s worth a shot,” Howard replied.

The guard released one of the prisoners and

handed him to Howard. Howard took the German to the field and showed him the mine. “Deactivate it.”

The German seemed to understand, and opened the mine. Everyone was worried about what would happen. Would the mine explode? Maybe the German would intentionally kill them. The mine beeped. It was deactivated, and they were safe.

The men went on to play baseball, carefully checking everywhere they stepped. They could now hardly run from one base to the next without worrying that they’d be obliterated any second. Fortunately, no more mines were found.

So next time you play baseball, be thankful you don’t have to worry about land mines. Howard was lucky to be alive. I bet it was the most interesting game of baseball he ever played.

* A mine is a bomb that is hidden in the ground or in water, and is meant to explode

on contact.

Paul Weir; Alabama, USA

Read additional stories from the 2013/2014 celebration:

Sneak a peek at Grannie Annie, Vol. 9 |

Ruth stood . . . and crossed to stand on the opposite side of the flag. Relieved, Lois felt convinced that she would not be punished for this lie. True, she didn’t get to hold the flag, but this way, unless some unforeseen crisis arose, she was safe.

Ruth stood . . . and crossed to stand on the opposite side of the flag. Relieved, Lois felt convinced that she would not be punished for this lie. True, she didn’t get to hold the flag, but this way, unless some unforeseen crisis arose, she was safe. My grandpa advanced through the dense woodland, thinking to himself that nothing could go wrong. He had nearly reached the inspection line, feeling he would get a favorable report from the inspector, when a seagull flying overhead dropped its load on my grandpa’s right shoulder. My grandpa frantically tried to think of something he could use to wipe the bird poop off, but he didn’t find anything. He couldn’t even locate a handkerchief. The only thoughts going through my grandpa’s head were thoughts of wonder and worry — thoughts like What will they do to me? and They’ll lock me up for sure. Because the troops weren’t allowed to talk, my grandpa couldn’t ask if anyone had a piece of cloth to wipe the mess off.

My grandpa advanced through the dense woodland, thinking to himself that nothing could go wrong. He had nearly reached the inspection line, feeling he would get a favorable report from the inspector, when a seagull flying overhead dropped its load on my grandpa’s right shoulder. My grandpa frantically tried to think of something he could use to wipe the bird poop off, but he didn’t find anything. He couldn’t even locate a handkerchief. The only thoughts going through my grandpa’s head were thoughts of wonder and worry — thoughts like What will they do to me? and They’ll lock me up for sure. Because the troops weren’t allowed to talk, my grandpa couldn’t ask if anyone had a piece of cloth to wipe the mess off.