Selected Stories from

The Grannie Annie Family Story Celebration 2011/2012

— Stories dated 1976–1990 —

1.

My Mom and the Birch-Tree Bridge

northern Wisconsin, USA; 1976

One clear fall day, my mom and her family were closing down the land that they owned on Round Lake in wooded northern Wisconsin. While my grandpa was busy taking down the pier planks for the winter, my mom and my uncle Dave decided to go adventuring.

They had been warned many times by my grandparents to never cross the birch-tree bridge that led to a Native American reservation on the other side of the rocky creek. However, on that warm and sunny day, my mom let her curiosity get to her. While my uncle Dave was smart enough to turn back, my mom walked straight past the no-trespassing sign and into the thick woods.

After a few steps into the woods, she saw a few old trailers, a very large fire pit, and two or three handmade totem poles. Feeling scared because she had crossed the old bridge, my mom turned back and ran home. Unfortunately, someone must have seen the very white blonde hair she had when she was young.

A few minutes after getting back to the family land, a loud pickup truck pulled into the dirt drive-up. Two Native American men got out and went to talk to my grandpa, who was still moving planks from the pier. My mom was worried they were coming to behead her!

Once they pulled away, my very upset grandpa told my mom that the reason the men had come was to make sure she was all right. They had animal traps planted throughout the woods on their land, and often bow hunted there as well. They were concerned for her safety. After realizing she wasn’t going to be on a totem pole herself, my mom decided the punishment for crossing the bridge didn’t sound all that bad. By the way, she mastered how to clean out an outhouse for the winter that day!

Nolan Bishop; Ohio, USA

(This story is also included in Grannie Annie, Vol. 7.)

2.

The Downfall of Joey Smernivak

Phoenix, Arizona, USA; c. 1977

Joey Smernivak*—ugh. Even the name gives me chills. Joey was the stereotypical bully at my dad’s old school—huge, angry, and always looking for a way to make your life terrible. But things were about to change. This is the story of how my dad and his best friend, Dano, brought “The Great” Joey Smernivak to his knees.

Some people overlook the true power of old World War I field phones, the only long-distance communication devices at that time. The field phones were very important during the war for transmitting messages from one post to another, as long as the phones were connected by wires.** But my dad and Dano found out that they could be so much more.

During Dano’s family vacation to Canada, he happened to stumble onto one of these rare field phones in an old thrift store, and a whole world of opportunity revealed itself. When Dano arrived home, it was all he could do not to sprint over to Mike’s (my dad’s) and show him the unruly power that the phone held within. But as it was late into the night, he was forced to wait.

The next morning Dano awoke earlier than usual and sprinted out the door to catch Mike before he departed for school. He turned onto Mike’s street and ran until the two-story stucco house was in front of him. He was still out of breath when Mike walked outside, but he managed to utter, “Look!” as he dove his hand into the blue backpack and pulled out the field phone.

Mike became giddy with excitement and asked, “What does it do?!”

Dano suppressed a queer chuckle and told him to hold the ends of the long wires connected to the top of the phone. He then slowly flipped the switch to turn it on and ZAP! An electric charge flowed from the phone into Mike, who through clenched teeth muttered, “Awesome.”

Before they could talk any more, none other than Joey Smernivak strutted around the corner with his posse of the dirtiest, roughest kids in school. He walked over to Dano and ripped the red and blue wires from his hand. “What is this? Just a stupid toy for you two losers? This . . . is . . . stuuuupid!” He then took the wires, shoved them up his nose, and turned around to the “gang.” “See guys? It’s just a kids’ toy.”

Time seemed to slow down in those few seconds. Dano glanced at Mike with a glint in his eyes and a joyous smile on his face. The click of the switch as Dano turned the phone on echoed out like the holy chorus, and electricity danced down the wires. Joey yelped, and his hair stood on end. He then ran down the street with the wires still stuck in his nostrils and the phone pulsating wave after wave of electricity through his body. Dano looked at Mike and said with an almost crazed look, “Awesome.”

* This name has been changed.

** The wires were strung above the ground or buried.

Will Klenk; Arizona, USA

(This story is also included in Grannie Annie, Vol. 7.)

3.

The Importance of Friendship

Denver, Colorado, USA; 1978

My mom, Ronit, has always told me to cherish my friends. I have always wondered what she meant by that. I realized what she meant when she told me this story.

It was the fall of 1978. Ronit and her family were moving from Tel-Aviv, Israel, to Denver, Colorado. Ronit was seven years old. Not knowing how to speak English was only part of the problem; she also would not have any friends and would have very little family.

On the day before they left, the bags were packed, and the house looked empty. Every picture on the wall was taken down. Every chair was gone. The air felt cold. The rooms felt empty, like an unpainted canvas.

“Why do we have to leave?” Ronit asked quietly.

The room was silent. No one replied.

“Why do we have to go?” Ronit asked again.

Ronit’s mother replied, “It’s for your father.”

After a flight that was twelve hours, Ronit and her family arrived in Denver. The air felt different, and everything looked different. The language sounded foreign. Ronit was confused and didn’t know what to expect.

School started a few long weeks after Ronit got to Denver. It was a small Jewish elementary school. The building was made of big bricks. The inside was very colorful due to the many pictures and worksheets on the walls. The building was stuffy, and there were many kids running around the hallways. Even though there were tons of kids and lots of colors, Ronit was not happy.

The entire class picked on Ronit. No one liked her. She sat in the back of the room, not knowing any word the teacher said. Even the Hebrew they learned sounded different from the Hebrew Ronit knew. During recess Ronit sat in the corner crying. She stared at all the kids playing on the playground. She wished she were back in Israel with her friends, playing on the playground.

One day Ronit went to school, and as usual she was sobbing. Soon she heard someone say, “Crybaby!” and point at her. Ronit realized the class had just given her a new nickname. Even though she didn’t know what crybaby meant, she kept on crying harder.

During recess, people approached Ronit but called her a crybaby. Then a girl about her height with freckles and pigtails came up to her. Ronit was ready for her to point and make fun of her, but instead the girl sat down next to her. Ronit was surprised. She stopped crying and wiped her tears.

“Shalom,” she said.

That day Ronit made a friend. From that day on, Ronit was excited to go to school. Even though Ronit and her new friend couldn’t communicate verbally, they used motions and hand movements to communicate. Ronit never cried again.

I now realize that you really need only one friend to be happy. The girl with pigtails was that one friend to my mom. This is also why you have to cherish your friends, because without them you wouldn’t be happy.

Arielle Williamson; Colorado, USA

(This story is also included in Grannie Annie, Vol. 7.)

4.

Blizzard of ’78 in a Small Town

Hoytville, Ohio; January 26–27, 1978

This story is a recollection of the “Blizzard of ’78” in the town of Hoytville, as told from the view of the Laberdee family. The dates of the blizzard were January 26 and 27, 1978. This is how the family survived the worst storm to ever occur in Ohio.

It all started when the weather forecast on January 25 called for severe snow. Sabra (my grandmother) and Tamie (my aunt) went to the store. When they came out, the rain had started to freeze. Tamie left to go back to college. Sabra was home alone with four children—a fourteen-year-old, a twelve-year-old, and two eight-year-olds.

The storm picked up, and the power went out, so the family closed off the living room to a 13- by 8½-foot area. They moved pillows and blankets into the room to keep warm, and they also used a small fireplace for heat. The back door of the house blew open during the night, and by the time Sabra got from the living room to the back door, the snow was knee-deep. She nailed the door shut so it would not blow open again. Also the storm blew out the bathroom window, so that needed to be boarded up, too. During the storm the family ran out of firewood inside, so they used the legs of a pool table.

After two days the snow stopped. To get outside, Rick (my uncle) had to go to the second story and climb out the window. He then had to tunnel down to get to the door of the house. Also after the storm, Sabra had the two older kids deliver food to neighbors that were low on food. She did not want people to go hungry.

After the storm, the drifts around the small town of Hoytville were as tall as houses. Lorrie (my mom) and Rick went to play with friends. They had a snowball war, hiding in the gullies of the drifts. Since they did not have any snow hills around, they sledded down the roofs of people’s houses. When they went out to feed the dogs one day, they discovered that the mother dog had brought a cow’s leg back to her babies.

After a couple of days the National Guard flew into the Hoytville area. They brought food and checked on people. They brought food such as peanuts and peanut butter. People from the town who had snowmobiles went to North Baltimore to bring back food. People went around to houses to check on neighbors. Tragically, two older ladies passed away from the cold.

In about two weeks the National Guard cleared the roads in Hoytville. Backhoes and dump trucks were used to move the snow. When they had finished, you could stand on the tops of drifts and look down on the tops of semis driving by. It took a lot of pulling together by the townspeople to survive during this horrible storm.

Robert Nicely; Ohio, USA

5.

Snow Sledding

northeast China; late 1970s

Have you ever had to work for the whole day? No resting, playing, or even stopping to stand for a while? My dad experienced this a long time ago.

During the 1970s my dad lived in Northeast China in a house no bigger than a log cabin. Every day he and his siblings would do lots of chores. During the winter, twice a week, the wood for the fireplace would run out, so my dad and his siblings would go to get some more. They would bundle up and walk outside. Then they would run as fast as they could up a not-too-steep hill, and there would be a small snow-covered forest at the top. The hill was not that far from the house. When they got to the top, they used their little axes, and they would cut down small trees. When they cut enough wood to last about a week, they would start to lug the logs down the hill. Since the logs were very heavy and the slope was very slippery, they would slip and fall down the hill instead.

So they decided that when they left the house, they would each stuff a thick rope into their pocket and take it with them to the forest. Now they would each get out their ropes and tie two logs together. When they finished, they would tie the rest of the trees they cut down onto the two logs. Then each of them would gather three or four small twigs and hop onto the sled they had made. Now they could slide down the hill and have fun!

My dad and his companions all had on thick coats with tons of layers. They would slide down the hill so fast with the cold wind roaring in their faces. They would use the twigs they had taken and stick them in the ground to steer them around boulders and sharp rocks poking out of the ground. When they got to the bottom of the hill, they stuck the twigs in the ground to slow them down to a stop. They could see their little cottage. Some warm tea sounded too good to be true. They grabbed the ropes and lugged the logs the rest of the way. This procedure took almost from lunch to dinner, and my dad still had a lot of work to do!

I have learned so much from this story about how you can always have fun while you work. I have used this story in so many situations in my life. This goes with a rule: Work can always go with fun!

Anna Cui; Missouri, USA

(This story is also included in Grannie Annie, Vol. 7.)

6.

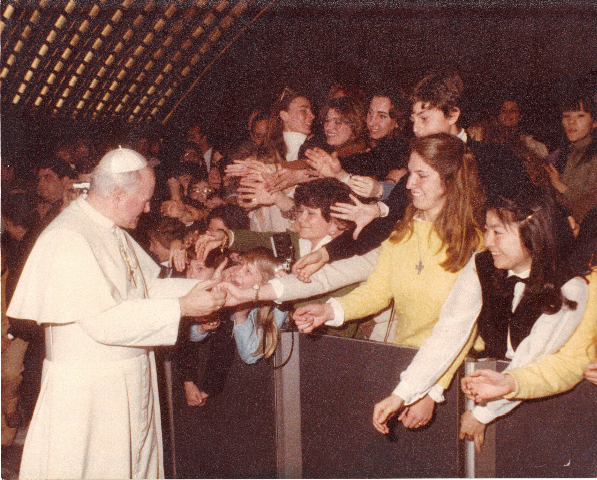

Touched by a Saint

Rome, Italy; 1980

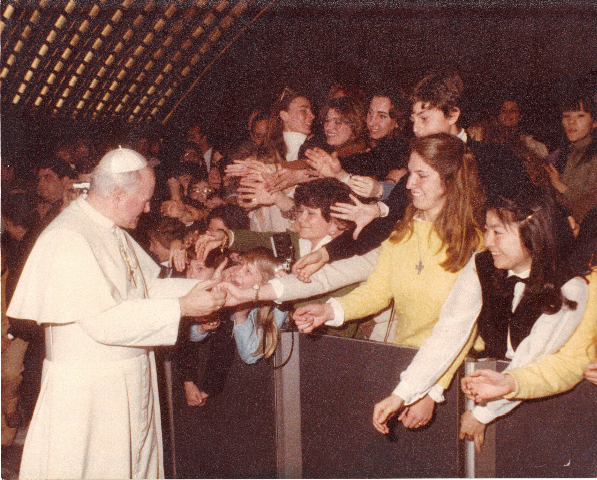

It was a bright, sunny day in Rome, Italy. My mom was living there for two years, because her dad was working for the American embassy. Mom was eleven years old when she went on a field trip with her school. This was no ordinary field trip though; she was going to the Vatican. The Vatican is a city within Rome where the pope lives. The pope is the head of the whole Catholic Church. At this time, the pope was John Paul II.

On the day my mom’s school went, the Vatican was very crowded. She was stuck way back in the crowd with her school friends and family. She wanted to get to the front of the aisle so she could see the pope walk down to the altar. Luckily, some kind people let her through to the front. As she emerged, my mom caught a glimpse of the pope walking down the aisle. He was shaking everyone’s hand and then shook my mom’s. Just like everyone else, she was thrilled!

When he was walking away, my mom shouted, “Kocham Cie!” which means “I love you” in Polish. Pope John Paul II was the first and only Polish pope. My grandma is 100 percent Polish, so this pope was very special to my family. My mom was shocked when the pope turned around, walked toward her, smiled, and put his hand on her cheek. That was a very amazing moment for my mom. The only sad part was that none of her family or friends got to see it.

Then about a week later my grandma got a phone call. It

was from one of her friends who had gone to the Vatican.  Her friend said, “Did you like that picture of Debbie and the pope?” My grandma was confused and shocked at the same time. Apparently, Vatican photographers had snapped a picture at the exact second that the pope patted my mom on the cheek. My grandma immediately went to the Vatican and bought the picture. To this day we still have the picture hanging up in our house. Her friend said, “Did you like that picture of Debbie and the pope?” My grandma was confused and shocked at the same time. Apparently, Vatican photographers had snapped a picture at the exact second that the pope patted my mom on the cheek. My grandma immediately went to the Vatican and bought the picture. To this day we still have the picture hanging up in our house.

Pope John Paul II died on April 2, 2005. He was eighty-four years old. He is on the way to becoming a saint, so because of that . . . my mom has been touched by a saint!

Alli Hanna; Ohio, USA

(Photo courtesy of the Hanna family. This story is also included in Grannie Annie, Vol. 7.)

7.

The Miraculous Journey to America

Tehran, Iran; 1981–1985

In spring 1981, my uncle Rahim sat alone inside his house in Tehran. He had been only ten when my father had immigrated to America. Rahim badly wanted to follow in my father’s footsteps because of the awful living conditions in Iran. There was a lot of cruelty and violence. A revolution started, and as a result, no one was allowed to leave, especially Jewish people. The government forced boys as young as seventeen to go into the army. My uncle wanted to immigrate to America as soon as possible, so he contacted my father and begged him to get him out.

In 1984, when Rahim was sixteen, my father and my grandparents paid $5,000 to smugglers to get Rahim out. Even though the plan was extremely dangerous, Rahim was willing to do it. He traveled three weeks with two other boys and an old man. For part of the trip, smugglers took him and his companions into the back of a 5,000-gallon oil truck that had been divided into two compartments so the men could sit. My uncle was terribly scared and was ready to turn back, but he decided to be brave and stayed.

The driver took an eight-day route to the border instead of a four-day route. He drove an extra four days, because he wanted to avoid a dangerous checkpoint. At that checkpoint the Iranian guards would have inspected the truck, and if they had found the men in the back, they would have shot them on the spot.

When they finished the ride, they were in Turkey, where the smuggler expected payment, but unfortunately the money hadn’t gotten there yet. The smuggler then kidnapped my uncle and his companions to try to get the money from my father. He held my uncle and his companions hostage for eight days. He stripped from them their extra clothing and money, and left them with nothing but a bus ticket.

The bus was fifty miles away, and they had no transportation. They had to walk fifty miles. They had no money, no extra clothing, no place to sleep, and no food to eat. Worst of all, their parents didn’t know where they were, and they had no way of contacting them.

My uncle and his companions went to a hotel, hoping an employee would let them use their phone. They were grateful and overjoyed when they were given permission to use the phone. They called their parents, who had been searching for them!

My uncle and his companions spent thirty-three days traveling to Istanbul, Turkey, then waited two months for documentation. My uncle was tired and scared, and he wanted to go home, but he kept going. It was like an underground railroad: They went from safe house to safe house, from contact to contact, along an invisible transport system.

A Jewish family in Zurich, Switzerland, let them stay with them for ten days, including all of Passover. After that, they went to their final stop, Vienna, Austria. My uncle and his companions stayed in Vienna for eleven months for U.S. visas. It took over a year, but finally he made it safely to the United States.

Eden Hariri; Maryland, USA

8.

My Opa Left His Fingers on Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania; 1990

When my opa (German for “grandpa”) was fifteen years old, he read a book titled The Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway. When he finished the book, he decided that sometime in his life he would climb Mount Kilimanjaro. He fulfilled that dream forty years later, when he was fifty-five years old.

In the spring of 1990, while vacationing in Thailand, my opa met another German man who was planning a trip to Mount Kilimanjaro in the fall. My opa decided to go on the trip, too. The tour they went on was an organized two-week safari that began at the base of Mount Kilimanjaro and finished with a three-day hike to the peak. Their guide on this trip up the mountain had taken about 400 trips before theirs. Obviously my opa’s guide knew the mountain well.

When my opa started his safari adventure, he was at sea level. By the time he reached the base of the mountain, he was at 1,300 meters. It took him about three days to get to the top of the mountain, not because it was such a long hike, but because he needed time to allow his body to acclimate to the altitude. After the first day, he reached 2,000 meters, where the climate was still tropical. The next day he reached 3,200 meters and saw mountain vegetation, like pine trees and bushes. On the third day my opa took an eleven- to twelve-kilometer hike along the ridge of the volcano. Once he got to the other side of the volcano, he spent the night in a hut on Uhuru Peak, which his guide called “the peaceful peak.”

The next morning they had to get up at 2:00 a.m. to climb to the summit. During that last climb, one of the lanterns they were using broke, and my opa thought he could help fix it. He took off his glove for two to four minutes in a temperature of 0 degrees Fahrenheit. That was a big mistake. My opa began to feel pain in his fingertips immediately, and by the time he reached the summit he realized he had frostbite in all five fingers on his right hand. The climbers reached the summit around 6:00 a.m. and stayed for about twenty minutes to celebrate. The guides even had a smoke and a drink. Then they began the hike back down—and my opa’s hands were hurting even more.

When my opa reached the bottom, his fingertips were black. He went to see a medic at the base of the mountain. The medic said he could not treat the frostbite, but he gave him some strong antibiotics.* When my opa got back to Germany, an American army doctor looked at his fingers and said he wanted to amputate them, but my opa said, “No way.”

The doctor wrapped the fingers and said they would never recover, but my opa didn’t believe him. Then about five weeks later all the skin and fingernails fell off. It took one year for it all to grow back and three years for my opa to get the feeling back in his fingertips. Even though my opa left his fingers on Kilimanjaro, he was able to fulfill one of his dreams.

* Antibiotics would help to prevent infection.

Kyle Ehlers; North Carolina, USA

9.

An Important Change

central Texas, USA; 1990

As a seventh grader living in the twenty-first century, I can honestly say no one has ever given me a hard time because my mother is white and my father is African-American. I have never endured racist comments coming my way; however, I can’t say the same for my dad. In 1990, racism was still a problem in the small Texas town where my parents were attending college. The university was predominantly white, as were the fraternities on campus. It was hard for minorities to feel comfortable, and even harder for them to join a fraternity.

My dad and six of his friends, who were all sophomores in college, decided this situation had to change and that they were the ones who could make this change happen. They met with the president of the university and told him, “Minority students aren’t comfortable here. We want to start our own chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha.” This organization is an African-American fraternity, and my dad and his friends thought it was important to bring groups to campus that celebrate different cultures. After some discussion with the university president and with the fraternity’s national headquarters, their request was accepted.

Starting this fraternity was brave of them, considering the environment of the college and the surrounding town. Just twenty miles away, the Ku Klux Klan, a group that has tormented and killed African-Americans because its members believe minorities don’t deserve freedom or equality, was active. The Klan wasn’t that violent in the town where my parents lived, but still, everyone was aware of its presence. The group sometimes held rallies nearby to remind everyone of its existence and its beliefs. Its members yelled slogans like “White power!” just to see if they could intimidate local residents.

Because of the racist atmosphere, my mother and father received dirty looks when they were out in public or on campus. People would say things to them like “You don’t belong together!” One time they were in a restaurant, and the waiter refused to serve them food. My dad had grown up on military bases his entire life. No one had ever treated him this way or called him offensive names. My dad thought that bringing in an African-American fraternity would slowly diversify his school, a change the school badly needed.

I can’t fathom why people would be racist. As my dad told me this story, I didn’t understand why my caramel-colored skin would make me a target of hatred. My skin color does not determine who I am or how I act. My dad showed me this in abundance when he helped start a chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha in a small-minded and slightly racist town.

Mahatma Gandhi said, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.” My dad and his fraternity embody this quote; they changed their campus and the mindset of the people around them. That change speaks for itself, and I’m glad to share my dad’s story.

Gabrielle Lewis; Texas, USA

(This story is also included in Grannie Annie, Vol. 7.)

Read additional stories from the 2011/2012 celebration:

View the illustrations in Grannie Annie, Vol. 7

Sneak a peek at Grannie Annie, Vol. 7

|

Her friend said, “Did you like that picture of Debbie and the pope?” My grandma was confused and shocked at the same time. Apparently, Vatican photographers had snapped a picture at the exact second that the pope patted my mom on the cheek. My grandma immediately went to the Vatican and bought the picture. To this day we still have the picture hanging up in our house.

Her friend said, “Did you like that picture of Debbie and the pope?” My grandma was confused and shocked at the same time. Apparently, Vatican photographers had snapped a picture at the exact second that the pope patted my mom on the cheek. My grandma immediately went to the Vatican and bought the picture. To this day we still have the picture hanging up in our house.